“Lorca’s confidence in his plays is palpable in this beautiful subtly that we seldom see on stage today.”

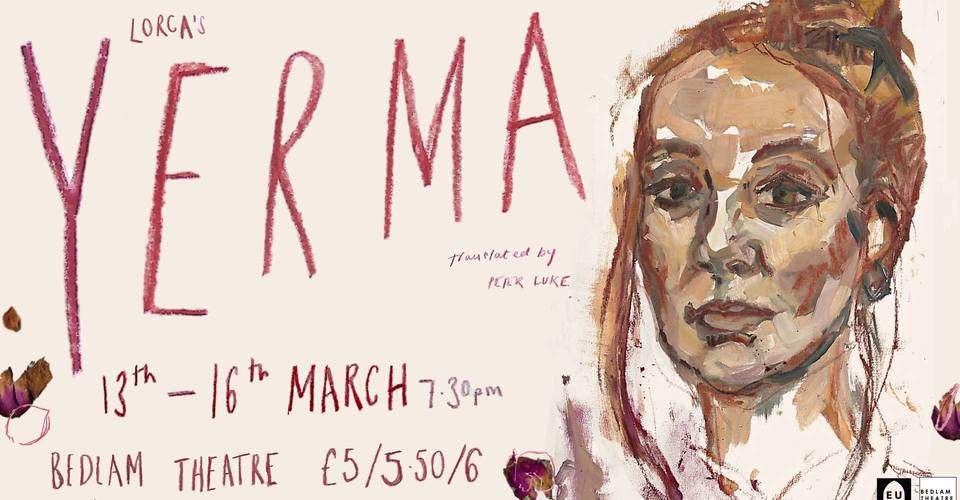

WHO: Jane Prinsley and Laura Hounsell, co-Directors

WHAT: “A young woman is driven to the unthinkable by her desperate longing to conceive a child. Yerma, meaning barren in Spanish, is tortured by her inability to conceive and becomes increasingly consumed and disoriented by her pain.

Federico Garcia Lorca’s 1934 piece challenged the social order of the time and the claustrophobic expectations of a rural Spanish village. It is relevant in our world of pressure and expectation, where women can be just as crippled by the judgment around them.

In this bold new multi-sensory adaptation, Lorca’s age-old themes will be rendered contemporary.”

WHERE: Bedlam

DATES: 13 – 16 March

TIMES: 18:00

MORE: Click Here!

Why Yerma?

Lorca’s writing is timeless. He manages to articulate the pain of lost love, oppression and unfulfilled dreams in a totally contemporary way. The roles he has written for female actresses are second to none and the atmosphere of claustrophobia that he creates is beautifully painful. It was an exciting challenge to do justice to his talent.

How will such a young cast, most focused on their studies rather than settling down to parenthood, approach the play’s central themes?

Whilst our actors’ lives have taken different paths from their characters, they are predominantly the same age. It is fascinating for us to explore the lives of young people in a different setting. Furthermore, the play’s central themes of social pressure and expectation is ageless. Most people feel the pressure of their surroundings and so actors have been able to draw on their own insecurities and uncertainty about the world they live in. Also as ambitious female students, motherhood is something which we must seriously consider in our future plans. Whilst we are currently focusing on our studies, the pressures of having a family and a success carer is ever present and pressing. The themes of motherhood, loss and societal pressure on women are as familiar to us as they are to the play’s characters and we will approach them with the truth of our own concerns.

This play is set in a society more claustrophobic and traditionally-orientated than our own. Will contemporary audiences relate to this writing as anything more than a historical curiosity?

The pressures on Yerma and Juan to be parents and to have a successful relationship may have become more subtle in the years between today and Lorca’s rural Spain, but these pressures very much still shape our lives today. Lorca was a modern thinker and knew that most women were not best suited to being a housewife, but the stereotypes he was fighting against in his literature are still apparent. We have chosen to stage the play in an atemporal rural setting so that audiences from around the UK will be able to draw on their own experiences and backgrounds. Audiences can look forward to seeing a magnified version of our society today, where the New Zealand Prime Minister is asked on the BBC if she would propose to a man and where our own Prime Minister’s shoes receive more attention than her policies. Motherhood and femininity is so interwoven with being a modern woman that Yerma feels as relevant now as it did in the 1930s. In our adaptation of Yerma we have focussed more on these central themes as opposed to the historicism and hope to transcend the original 1930s setting.

The production is billed as a “multi-sensory adaptation”. What can we look forward to?

You can absolutely look forward to the music. Singer-songwriter Eve Simpson is joining our cast as an actor-musician and she has set Lorca’s poems to music. Oftentimes Lorca’s poems are cut or spoken, but we have tried to remain as true to his intentions as possible by having them sung. Furthermore, to create our atemporal aesthetic, Eve Simpson and Robin Gage have drawn on musical traditions from across the British Isles and some Flamenco styles. We really are trying to create something multi-sensory, so also expect beautiful scents, visions and sounds in this production.

How does Yerma fit into the rest of the season at Bedlam?

The Bedlam season is varied and uncurated which is one of our many strengths. Yerma will bring innovation, music, joy, thought and opportunities for brilliant female actresses. It is exciting to overcome the challenge of staging a famous and loved play, which incorporates verse and prose and spoken and sung, but it is something that we as directors, our creative team and our talented cast have all relished. This week, Abi Morgon’s 2011 play Love Song is on at Bedlam and draws on similar themes of love and motherhood, so Yerma follows nicely. It is a coincidence that similar themes are being covered in both weeks, but perhaps the Spring weather has got us all thinking about fertility…

If you could ask the playwright a question, what would it be? What do you think he might answer?

How did you manage to write such convincing and tragic female parts? How were you able to articulate the female struggle in the Andalusian rural villages so perfectly and did you know at the time that you were creating something universal? Lorca was homosexual and a socialist and was seen as a threat to the far-right nationalist forces who murdered him. Perhaps his own struggle and isolation is written subtly into the women (and men) in his plays, who deal with repressed love, broken dreams and the feeling of being trapped.

What’s the one thing everyone should know about Lorca?

His fearless politics and how that manifested itself in his art, both as a writer and a painter. For Lorca, his art was a lifeline and one that cost him his life.

Is Yerma as good as Blood Wedding?

What a strange question! They are often printed together, along with The House of Bernarda Alba, and are sometimes billed as a rural tragedy trilogy, although that is to forget Dona Rosita the Spinster, another masterpiece. All of these plays have different plots and characters, but there is usually a woman fighting against expectation, oppressed love, an imposing older woman and men who seem lost. They are all reminiscent of Greek tragedy but feel distinctly modern. Yerma is our favourite because of the central theme of motherhood and the pressures around parenthood that do not seem to have changed since the 1930s. The play’s rapid energy and descent into madness was also something we were captivated by when we first encountered it. It is like a train that speeds towards its final crash.

Are there living artists who can hold a candle to Lorca and the Generation of ’27?

Lorca continues to inspire artists and creators but people should always read more of his work as it is rare to find words rendered as beautifully as his. We found a recent modern staging of Yerma to be contrary to the original aim of the piece as we love how the pain that Lorca portrays is elegantly told. His work is often simple and important action can happen offstage. Lorca’s confidence in his plays is palpable in this beautiful subtly that we seldom see on stage today.

What’s the one thing you know now, that you wish you had known at production’s start?

Collaboration is great. We’ve worked so much better together than we could have ever done individually. It is brilliant to bounce ideas around, disagree, agree and improve our work together. Going forward, we will always look to work in a collaborative style, both on the creative team and with actors.

LIKE WHAT YOU JUST READ? FOLLOW US ON TWITTER! FIND US ON FACEBOOK! OR SIGN UP TO OUR MAILING LIST!

You must be logged in to post a comment.